Vibrissae

Beginning a Substack platform is a delicate act. I feel a bit on my tiptoes—navigating a space of ether, rather than grounding my feet on the more solid earth of a face-to-face conversation. I toss an etheric line out into space… and hope for connection.

An ex used to call me an animal. She meant it in the sense that I tend to navigate the world in more sensory, tactile fashion than many people. I prefer to write in longhand, using a fountain pen and a Moleskine notebook. I prefer to walk than be in a car. My visual receptors are actually my weakest senses. I sniff almost everything and have a distressing tendency to touch things with my tongue. I rub my skin against the world; I cock my head and listen for signals and signs. In this life, I feel my way.

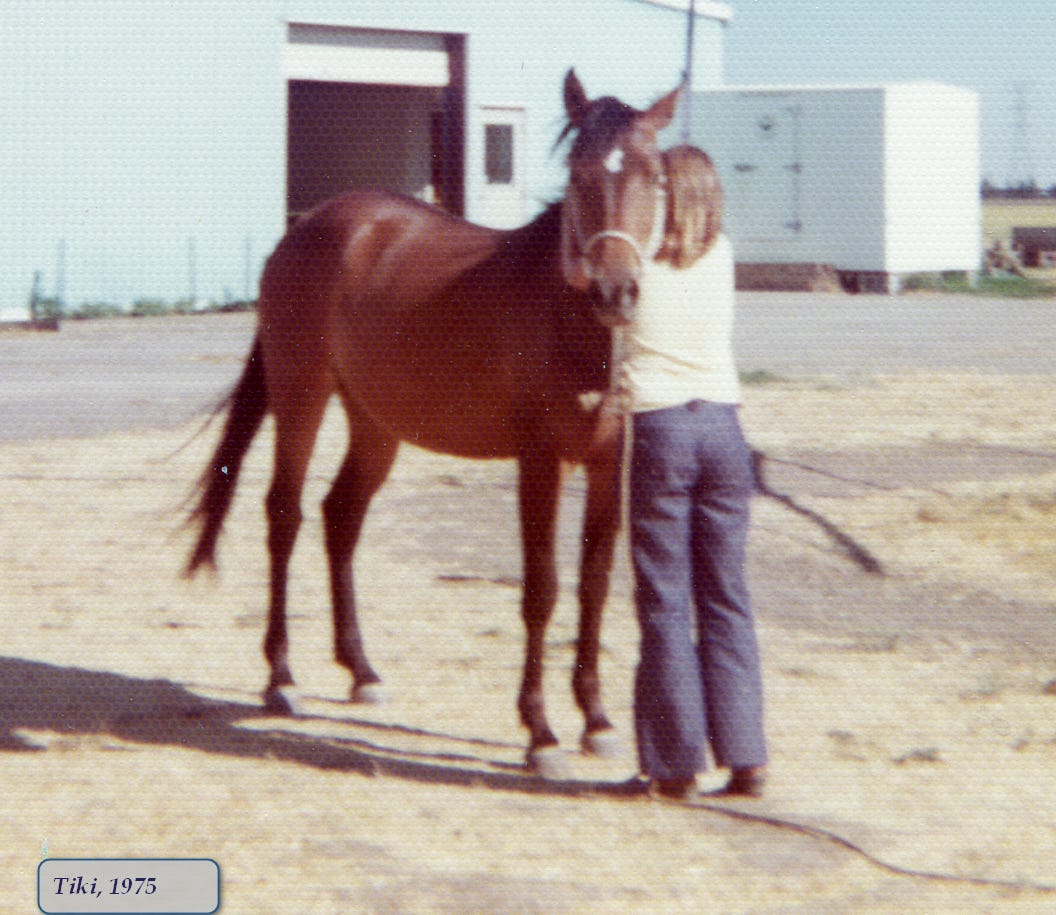

This Substack is about another animal; beings I love with the blind devotion of a child.

This particular Substackian character is one many people are fairly unfamiliar with these days, save for seeing them in pictures or films, or catching occasional drive-by glances at them standing pastorally in pastures. Perhaps you petted a small one at a kid’s birthday party—or had An Encounter that time you made the bad decision to take a ride on the beach in Mexico during spring break. You wore your cute bathing suit and floppy sun hat, and there was sand stuck to your legs and sand on the wet leather saddle, and your ass and thighs were ground to pulp and you got so chafed you decided to get off the thing, and when you began to slide off its back your sun hat blew off your head and under its hooves and it spooked and pitched you into the air. It yanked the reins from your hand and ran away up the beach, bucking and farting, and then you had to walk all the way back to the ratty little palapa where they rented the skinny, ugly creatures who, you decided as you sobered up during the long, hot, uncomfortable walk up the beach, were just the worst ever, unsafe and unfun, and why would anyone want to spend any time at all with them?

This Substack is about horses.

It’s also about love, and how love and horses intertwine.

I love horses. I have loved them since I was very small. I expect I will love them always. I love the way they look and the way they smell. I love their power, their grace, their fleet awareness. I love how they are in the world. I love how they are an ancient species that has evolved amidst so many climate changes and challenges over 56 million years to become the horse humans know today.

I am humbled at how Equus caballus has agreed, miraculously, to be in partnership with Homo sapiens for thousands of years. I am in awe of their generosity.

And, okay, I have been bitten, smashed, kicked, thrown, bloodied, and bruised by the objects of my affection. A deep relationship with horses is not for the faint of heart. It requires honesty, personal work, awareness, preternatural patience, softness, kindness, and infinite curiosity. It requires training, and thinking. Horses can drive you absolutely bugshit crazy. They are mighty and they are fragile. They can empty your pocketbook. They can make you furious and frustrated just by being, you know, horses.

To be honest, in my horsehuman journey I am just beginning to understand what richness horses offer in terms of communication, grounding, and presence.

This Substack will talk about all of that, from the physical to the metaphysical . Horses and humans are still intertwined, even if we—staring down at the phones in our hands, infinitely captured by cyberspace—have forgotten the real necessity of what equines offer.

One thing you may or may not know is horses have whiskers around their muzzles and eyes that are tactile organs. These whiskers are also known as vibrissae (the plural of vibrissa). The word vibrissa comes down to us from the Medieval Latin “vibrare,” which means: "to brandish," and "to wave." (Merriam-Webster, how I love thee!)

Equine vibrissae are fascinating. There are two types: macro-vibrissae, which are thicker and longer and help determine distance and width of an object—Huh. What is that round thing in front of my nose?—and micro-vibrissae, which are closer to the mouth. These little dudes are shorter and thinner and used for object recognition—Hey! It’s an apple!

Why are they so important? Well, due to the long equine noggin and the way horse eyeballs are placed well to the side of the head, horses have a big blind spot literally in front of their noses. Want to know what that’s like? Put your fingertips together in the shape of a capitol A and rest the peak of the A over your nose. Look down. Isn’t it interesting what you cannot see? Now, put an apple on your countertop. Keeping your fingers atop your nose, bend your head and try to grab that apple with your teeth. Hmm. Wouldn’t it be handy and evolutionarily important for you to have long hairs around your mouth that tell you what the apple is and how far it is from your lips and teeth?

Each equine vibrissa is embedded in a blood capsule that has a lot of nerves. Every movement of the whisker is perceived by sensory receptors that shoot intel directly up to the brain of the horse; information that tells them an enormous amount about their surroundings and fellow creatures—Is this thing hard or soft, edible or not? How close is it? Who are you? And although there is not a lot of hard data about equine vibrissae, as opposed to, say the whiskers of manatees and mice, there is strong data that says horses are more prone to eye and head injury when vibrissae are trimmed.

When I was a kid I showed Morgan horses. At that time, we shaved every whisker from the horse’s face, and clipped the insides of their ears to bare skin. Wanting our horse’s faces to have the perfectly-smooth appearance of a shaved Olympic bodybuilder, we didn’t know just how badly equines need those long fuzzy hairs and how damaging it could be to take those tactile organs away from them.

It’s better now. Regulatory agencies in equine sport are banning the clipping of vibrissae, and more and more horse folk are deciding to embrace the fuzz and delicate dance of the long hairs around their horse’s mouth and eyes as something special and necessary for equine well-being. And if you haven’t fallen in love with the appearance of frost coating your equid’s whiskers in the winter, put your fingertips back above your nose and give yourself a little aide-memoire as to their importance.

Sending writing out into the world for public consumption in a Substack is a bit like having vibrissae. I am blind to you in many ways. You are blind to me. We meet in this argot called written English, and within the sensitive tendrils of the words I write and the words you read (or hear) we manage to touch, to share images and ideas.

When I talk about love, I talk about horses. It’s a curious obsession, and one I hope you enjoy.

Welcome.

Oh you are singing my heart song!!

Learning so much already! Also, I totally put my hands over my nose as instructed and tried to eat and apple.